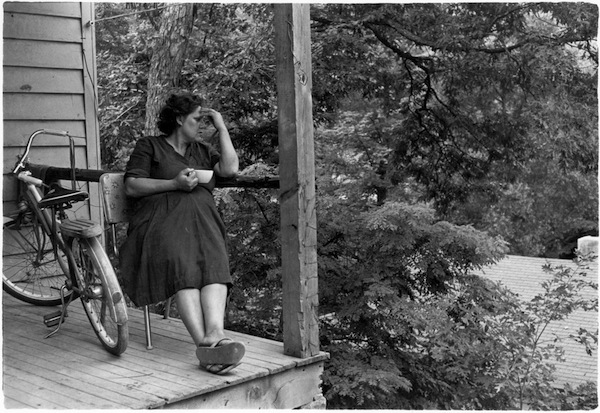

Exactly 40 years ago this week, William Gedney returned to the hills of eastern Kentucky to reconnect with the Cornett family (pictured above with Gedney) whom he had spent more than a week with in 1964 (see below). The relationship between Gedney and the Cornetts is described in this beautiful vignette from What Was True: The Photographs and Notebooks of William Gedney coedited by Margaret Sartor and Geoff Dyer:

“We though of him as one of our kids. He was just a plain person, like us. At the store, Bill’d say to the kids, ‘Do you want an ice cream? If you do, get one.’ He wouldn’t say, ‘Go on, get an ice cream.’ You could get along with him.” On the day Gedney arrived, he told Willie he would sleep on the floor and offered to pay two dollars a day for his keep. Willie refused the money, but at the end of Gedney’s eleven-day visit, found exactly twenty-two dollars left behind. After telling me this story in the spring of 1998, the still lively, white-haired Willy added casually, “He could’be come and stayed a lifetime, it would’ve been OK with me.”

Thirty-five pages of What Was True are dedicated to Gedney’s time in Kentucky, including twenty-seven photographs (ten from 1964 and seventeen from 1972) and snippets of correspondence with Vivian Cornett. Sartor continues:

“The Cornetts remained in touch with Gedney for more than fifteen years. Their letters, most of them from Vivian, were among his belongings when he died. Over the years, he sent them prints and sometimes money. Vivian wrote back with family news and included school photos of the children. On one particular occasion, fulfilling a promise made to himself, Gedney sent Willie and Vivian exactly half of the seventy dollars earned from selling his first Kentucky photograph, the one of the girls peeling potatoes in the kitchen.”

Three girls in kitchen, appeared on the cover of the Fall 1996 issue of DoubleTake.

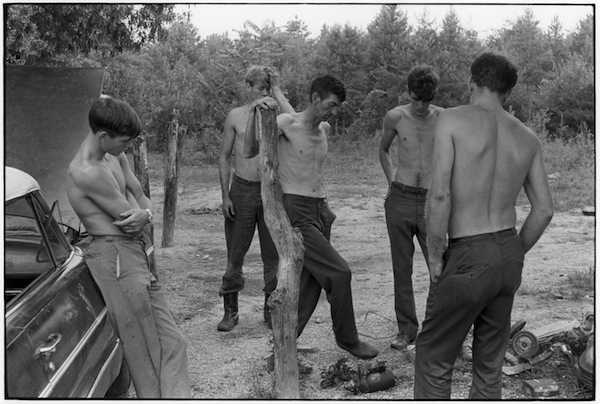

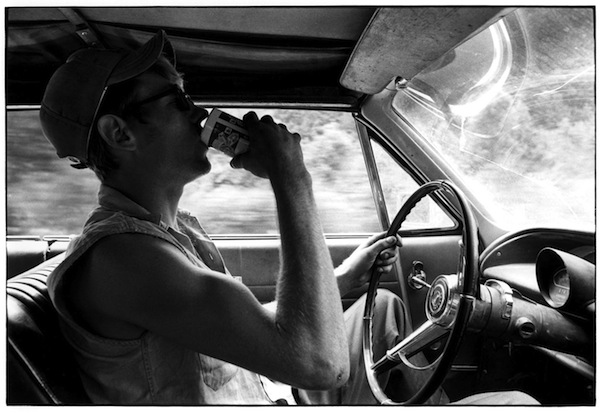

“The excerpt published here is from the trips Bill made to eastern Kentucky in the 1960s and 70s. There he spent most of his time photographing one extended family. In his life in Brooklyn, Bill was an eccentric; he was even described as a kind of recluse by some of his friends. But as a photographer he made profound connections with the people he photographed. In these Kentucky photographs we can see that he is fully engaged with these hill people, with the lives played out in and around their cars and porches. The sensuality in these pictures reminds us of our sameness and, in fact, what is beautiful about our sameness.” – Thomas Roma, DoubleTake, Fall 1996

“For several years now, I have looked through thousands of William Gedney’s photographs, read his letters, scanned his appointment books and grant applications, studied his notebooks and his journals. In my mind, I hear his voice, deep and articulate. After some time, I could also hear the silence, what was held back, hints of an unreachable place. In the photographs, this tension is part of their power – the cup half-empty. And the body revealing what the heart might want – and want to hide.” Margaret Sartor, What Was True

All black and white images (11) – William Gedney Collection, Duke University David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

William Gedney’s work never ceases to command my attention. It isn’t forceful, overbearing, or gimmicky. He presents grace, beauty, and humanity in a people often marginalized and dismissed. These are things that are important to me, qualities he captured from the people and place that means so much to me. He didn’t shy away from poverty or hardscrabble existence, instead he chose not to make it the focus of his work. Because of that, we get to see something so few who make photographs in Appalachia can show us. By pressing in close enough, quietly enough, in the words of Thomas Roma, he captured the beauty of our sameness.

Editor’s Note: I’d like to thank Margaret Sartor for her time and willingness to answer my barrage of questions about William Gedney. Additionally, I would like to thank David Pavelich, Head of Research Services, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University for his assistance in securing permission to use the images in this series as well as Amy McDonald, Assistant University Archivist, who cheerfully assisted me with box after box of Gedney’s prints, contact sheets, and notes. Last, but certainly not least, huge thanks to Chris Sims at the Center for Documentary Studies for the generous, long-term loan of What Was True.

Elsewhere: Ahorn Magazine featured some of Gedney’s work here. It’s well worth a look.

I love looking at these photographs they remind me of a simpler time. Of home thank you Mr gedney. For printing. Them. You were a man of. Grand stature