The last couple of weeks have brought about several interesting online conversations about Appalachia and what it actually looks like. While some time has passed since CNN ran Stacy Krantiz’s photographs, I think it’s important to continue to the conversation about the broader visual representation of Appalachia.

Before moving on, I want to share some additional thoughts on the CNN/Kranitz controversy. Last week, Kranitz sent me the 33 photographs she originally submitted to CNN (below). You can see the rest of her series from the project “Old Regular Mountain” here. From these, you get a clearer idea of what she chose to submit. What is still missing, however is why Kranitz chose these specific images.

Here’s some of what she had to say about her original submission:

CNN asked for me to send images to choose from. They did not specify the amount. I sent 33 images. I sent two options for: Cherokee, North Carolina, the Snake Handlers in Jolo, Scenic views of the mountains, Old Regular Baptists, swimming holes, and the Klan – because I thought they were important representations to include.

CNN front-loaded their edit with, in my opinion, a sequence of images that set up the ensuing controversy that, let’s face it, everyone expected. Was their goal to be controversial? Probably. Have they received a lot of clicks (by the way, clicks = advertisements = revenue) and comments about this picture story? Yes. One of the important things I’ve learned in writing about this specific instance (and there are many others) is that my own expectation of the media is unrealistic. I have gradually, and lazily, allowed myself to expect the truth from mass media, which is abhorrent and a whole different series of blog articles. Moving on…

In the days following, Kranitz said:

The photo editors at CNN responded and showed genuine concern for my desire to have the project presented in a way that was true to my intentions. While so much of the damage has already been done with so many people seeing the original sequence of images I appreciated that the editors where immediately responsive to my desires to change the edit to be more accurate to the project.

And the 16-image re-edit:

Finally, Kranitz has been nothing but transparent with me about the process and has taken responsibility (rightly so) for the fallout. I think there’s something to be said for that. In all of this, the only public acknowledgement from CNN I’ve been able to locate is in an article by Poynter’s Steve Myers:

CNN spokeswoman Erica Puntel said that CNN.com had chosen 16 of the 33 images Kranitz submitted, and that someone from CNN called to listen to her concerns. Puntel said by email:

[Kranitz] said that she had received a large amount of negative feedback and was concerned. She also said that she felt that the edit of the photographs did not represent her work in the way she had intended.

After some discussion, we agreed with her point that some people could misconstrue what she was trying to convey, and therefore, we changed it.

We must not overburden photography with something it cannot do – providing us with an accurate portrayal of anything. Instead, we must acknowledge the maker’s hand, and we should talk about its role – and our reactions.

But what about the framework of how we “look at” Appalachia? How has our view (yours and mine) been constructed? I think most of how we see pictures from Appalachia today coincide with the early War on Poverty images. Poor, white (and black) folks, shoeless, dirty, toothless, destitute. Charles Kuralt’s 1964 CBS feature “Christmas in Appalachia” comes to mind. Any honest look at Appalachia would yield those sorts of pictures at any point in time. Pretending that poverty doesn’t exist, or choosing not to photograph the systemic issues of poverty, don’t simply make them nonexistent. Nor do they accurately represent a place as a whole.

Perhaps the intent of some of the historical images of Appalachia are more of a survey of poverty rather than a survey of Appalachia. But I think somewhere our cultural and visual lexicon has made the two synonymous; Poverty = Appalachia and Appalachia = Poverty. In order to deconstruct that myth, it’s important to understand how it was constructed, which can’t be done unless we take a long look at the history of extractive industry in Appalachia. Human resources have always been of lesser importance than the natural in Appalachia. Coal and timber have trumped, and continue to trump, the welfare of the people.

John Edwin Mason noted, in a recent email discussion, that at the time of the earlier Appalachian photographs, folks “weren’t perhaps as sensitive to questions of representation as we are now.” He pointed out that “War On Poverty photographers were overtly engaged politically –on the side of the angels, as people like me would see it.”

And certainly photographs were being made in Appalachia prior to 1964.

Walker Evans – Farm woman in conversation with relief investigator, West Virginia, 1935.

Since the controversy of CNN’s edit of Stacy Kranitz’s photographs, I’ve taken a lengthy look at some of the Appalachian photobooks I have on my shelf in an effort to compare and contrast different photographer’s work in the region. This is by no means a complete list, but by spending some time in the four books listed below, some common themes about how Appalachia is represented emerged. For example, three of the four photographers are not from Appalachia (insider vs. outsider). Two of the four books include images of the KKK (stereotypical). None of these works tell the complete story of Appalachia (nor would I suspect their authors to claim), but rather their own idea and image of Appalachia. I would argue that there are elements of truth in all of these, but as Colberg points out again in “Photography and Place“:

Even if we assumed that it was possible to get that infinity of photographs of a place, two people would probably still come to very different conclusions. Just imagine someone living in the place and someone visiting. And that would be just the most obvious difference one could think of. As I’ve already argued elsewhere our perceptions of photography are very much based on what we bring to the table, our personal, cultural, political biases.

Some Appalachian photobooks:

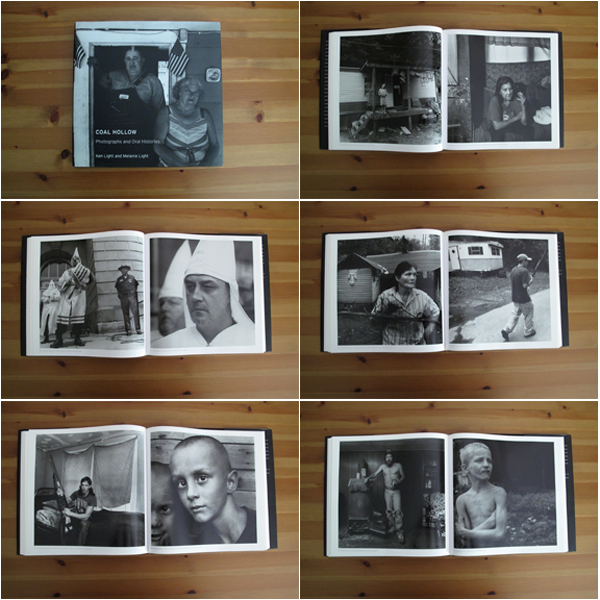

Ken Light’s Coal Hollow

2006, University of California Press

Hardcover | 152 pages | 11×11″

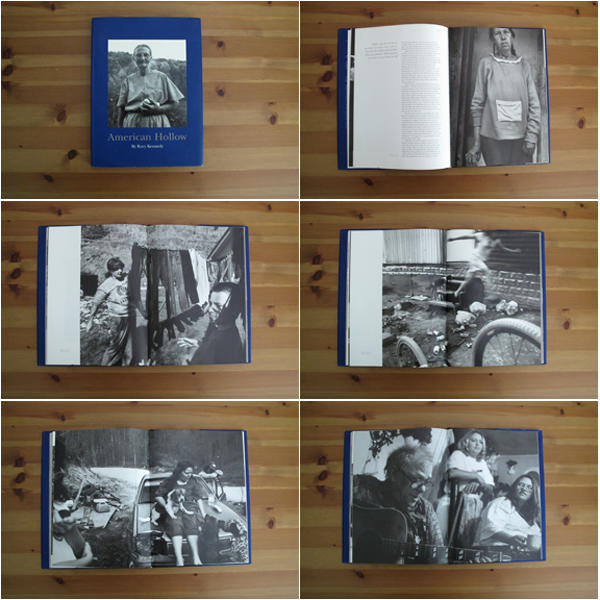

Rory Kennedy’s American Hollow

1999, Bullfinch Press

Hardcover | 128 pages | 8.5×11″

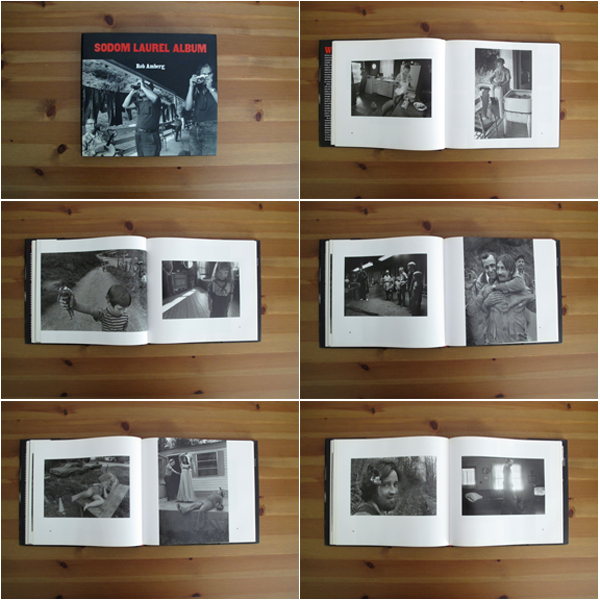

Rob Amberg’s Sodom Laurel Album

2001, University of North Carolina Press

Hardcover | 192 pages | 10×9.5″

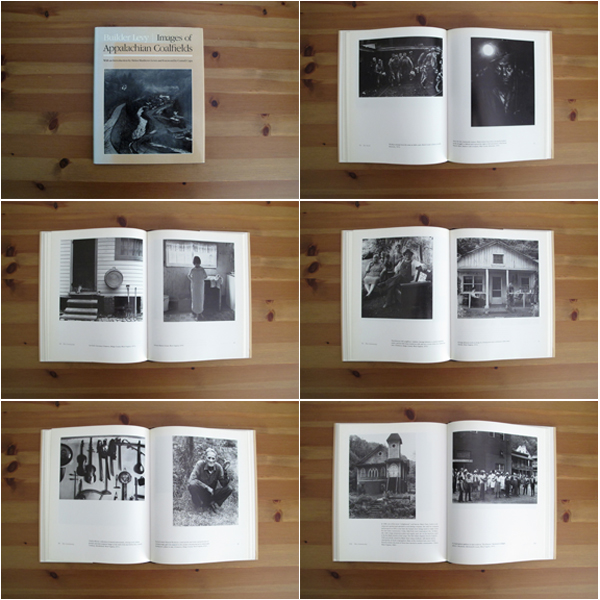

Builder Levy’s Images of Appalachian Coalfields

1989, Temple University Press

Hardcover | 144 pages | 7.5×9.5″

Moving forward, I’ll be writing more about the broader visual representation of Appalachia, looking at more photographs – new and old – from the region, and hopefully fostering good conversation about how and why we look at Appalachia and what that means.

Great post! The thoughts and points you shared make me want to respond in so many different directions-it’d take me all day : ) But I’ll narrow it to a few:

*To me-the majority of Kranitz’s photos show the expected stereotypes common to Appalachia. The subject is so close to my heart-maybe I’m not being objective about her series-but my gut reaction is her photos while executed brilliantly are just more of the same dribble about Appalachia.

*The quote you shared from Colberg is true. I take photos for my blog almost every day-and I’m always thinking of how they will be perceived by others.

*Love the question-you offered-how do we ‘look at’ Appalachia. When I first started the Blind Pig-I did a post about just that. Even though I’m beyond proud of my Appalachian Heritage-when I thought of the word things popped into my brain that had no context in my life as a native Appalachian. Noted writer and historian, Michael Montgomery, once said even though he lived in Appalachia-he always thought Appalachia was some remote area-far removed from where he lived in East TN.

*As I look at Kranitz’s photos-and the ones you shared from the books-I don’t think they staged the photos-in other words I believe those people live in Appalachia-I believe I could find similar subject matter here too. But the more controversial images are not the norm for Southern Appalachia where I live-nor would I believe they are the norm for any part of Appalachia. I also agree with the second quote you shared from Colberg. But-I guess where I get hung up is this: If those stereotypical photos of Appalachia are true-and deserve prominence in the mainstream media whether I enjoy them or not-then surely my true take on my life in Appalachia deserves the same prominence. However-the positive pictures never seem to garner the same support as the controversial ones.

My writing about Appalachia is almost always directly connected to my daily life-that’s the only way I feel qualified to write-about something I know. A recent occurrence in my life throws the stereotypical photos on their ears. I live in one of those hollers often talked about when one mentions Appalachia. I live in a mountain holler where all the houses are owned by different members of the same family. If you want to go even farther into the stereotypes-there are a few junk cars around, a few hound dogs on the loose and worn footpaths between the houses. The folks who live in my holler-live paycheck to paycheck-not one of us would be considered wealthy. Yet we are wealthy. We have jobs-we take care of our own-we work for our communities-we enjoy our lives. Two boys from our mountain holler who grew up with the folklore-the music-the food-the dialect of Appalachia were awarded full ride scholarships to Yale.

In a nut shell-that’s what I want people to know about Appalachia-that it’s possible to hold onto our heritage-onto our colorful dialect-our toe tapping music-our fascinating folklore-and onto our delicious food history and still make it in today’s modern world. My nephews-one a rising junior at Yale-the other a rising freshman of Yale are living proof.